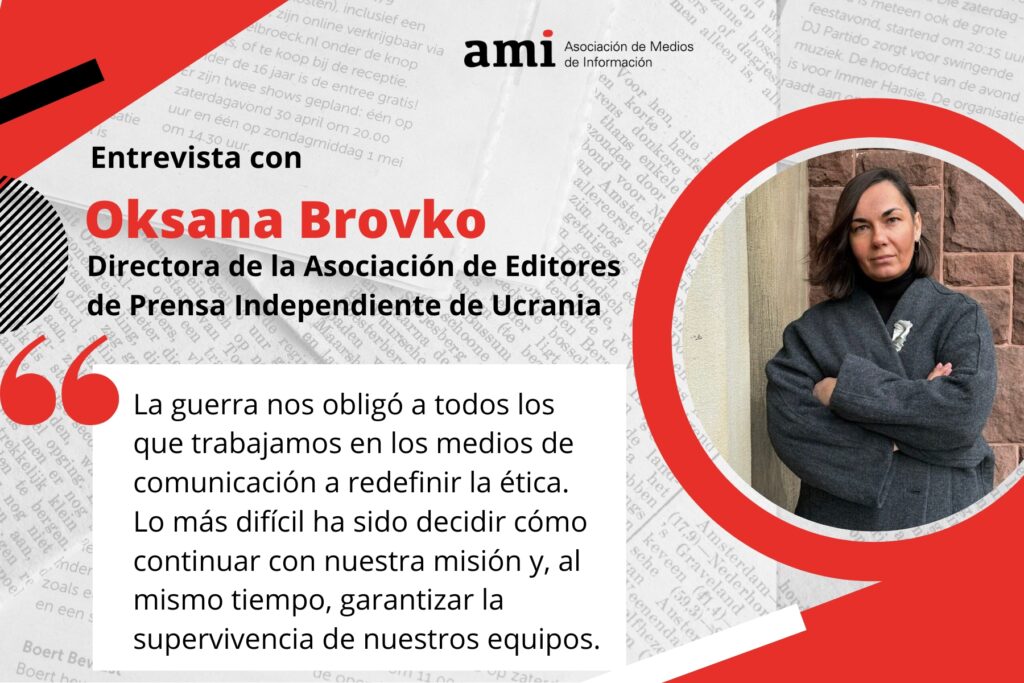

Oksana Brovko, awarded in Spain for her defense of press freedom, analyzes the challenges facing journalism, Europe’s solidarity, and the threats of disinformation. An interview originally published by Aquí Europa.

In early November, Madrid hosted the 20minutos Awards ceremony — an annual event that honors individuals, organizations, and communities that make a significant contribution to the development of society, culture, innovation, and freedom of expression. Oksana Brovko, Director of the Association of Independent Regional Publishers of Ukraine (AIRPU), received this award from King Felipe VI of Spain for her contribution to the development of independent media in Ukraine. It was on this occasion that she gave an interview to Aquí Europa, the translation of which we are pleased to present today.

***

Conducted on November 6, 2025, at the Hotel Las Meninas in Madrid, this interview with Oksana Brovko, a leading Ukrainian journalist and media professional, took place shortly before she received an award recognizing her extraordinary work in defense of press freedom and resilience under wartime conditions. In this in-depth conversation, Brovko reflects on the meaning of this recognition, the challenges faced by Ukrainian journalists, and the importance of preserving truth and European solidarity in the face of Russian aggression.

As part of her visit to Spain to receive the 20 Minutos Award, granted by Henneo — a group that is part of the Association of Information Media (AMI) — Oksana Brovko, executive director of the Association of Independent Press Publishers of Ukraine, speaks with Aquí Europa about the role of journalism in times of war, the resilience of Ukrainian media, and the importance of international solidarity in defending press freedom.

A key figure in the European media ecosystem and a member of the Steering Committee of WAN-IFRA, Brovko leads from Kyiv the network that brings together local and regional media outlets that continue reporting under Russian fire. Her voice, recognized globally for her commitment to editorial independence and the safety of journalists, embodies the struggle of Ukrainian journalism to survive and keep telling the truth amid devastation.

In this exclusive interview, Brovko reflects on the price of freedom, the challenges of practicing journalism in the midst of war, and the need for Europe to keep its attention on Ukraine. She also shares her perspective on the common challenges facing media around the world — from economic sustainability to the rise of artificial intelligence — and highlights the role of press associations as support networks and defenders of the right to report.

Aquí Europa: First of all, congratulations on the award you’re receiving today. What does this recognition mean to you personally, especially at a time when your country is still at war?

Oksana Brovko: Thank you. This recognition is a very important opportunity for me to remind everyone of the price of freedom that we are paying. In Ukraine, we are now fighting for the most basic values — for independence, for the right to be who we are, to preserve our nation. And through this war, we have understood that freedom is not something you are born with and can take for granted. Sometimes you need to defend it, you have to fight for it, and sometimes you even have to die for it. Many of my friends, colleagues, and ordinary Ukrainians are doing exactly that today. It’s very hard, but at the same time, this recognition gives me the voice to remind the world of what is at stake.

Could you tell us a bit about those first moments of the invasion — what it was like for you personally, for your family, and how you found the strength to move forward after losing almost everything?

Even before the invasion began, I was trying to be prepared, because everyone could feel that a full-scale attack was in the air. I knew I couldn’t control what was coming, but I wanted at least to do something. Two months before February 2022, I booked a small hotel in western Ukraine, near the Polish border, so that if the worst happened, I would have a safe place to take my children. I have four kids, and at that time, three of them were very young — the smallest was just two years old. As a mother, my main concern was to keep them safe, because I was sure that if Russian troops reached Kyiv, we would all be in danger. Professionally, I was also trying to protect my colleagues from regional media. We had regular meetings to prepare protocols — how to evacuate newsrooms, how to delete sensitive data about journalists from servers, how to keep teams safe. But when the full-scale invasion began, we realized that we were not really prepared. The first hours were the hardest — terrifying — because we didn’t know how big this would be. Would it mean nuclear strikes? Chemical attacks? Bombings? Or just ground troops crossing from Russia or Belarus? That uncertainty was the most horrible feeling. But having even a basic plan helped. Within hours, I packed my family into one car, and we drove to the western part of the country. Then I started calling colleagues to coordinate evacuations for newsrooms near the front lines. Those first hours and days were chaotic, but at least we were doing something — trying to save lives and keep journalism alive.

You have continued working as a journalist throughout this period, even transforming your work into a tool of resilience. What kept you motivated?

The motivation is simple: we just want to live in an independent country and preserve our right to be Ukrainians. That’s all. We want to live under a peaceful sky, to provide safety for our children and for our future. Every action, every decision comes from this understanding. We want to live freely on our own land, and we are ready to fight for it. Personally, journalism is my way of fighting — of documenting the truth, of helping people understand what is happening to us.

What are the main difficulties for journalists working from Ukraine today?

It’s a huge challenge. Journalists are constantly under attack — Russian drones, missiles, targeted strikes on media offices. But war, paradoxically, has also created opportunities. It has shown who our real partners are. From the first days, we received countless calls, emails, and messages from colleagues across Europe asking how they could help. This solidarity gave us strength. For the Ukrainian media community, especially local and regional outlets, it meant new contacts, partnerships, and friends. Not just professional contacts — real human connections. And this cooperation is helping us raise our professional standards. We face the same challenges as European journalists — artificial intelligence, engaging audiences, dealing with social media platforms — but with one more, crucial difference: we are working in the middle of a war. Even if you are far from the frontline, nowhere in Ukraine is completely safe. Russian missiles and drones can reach even the western regions near Poland. So every journalist here works in a constant state of danger.

How would you describe everyday life in Ukraine now, almost four years after the start of the full-scale invasion?

For us, this is actually the eleventh year of war, because it started in 2014 when Russia occupied Crimea and parts of Donbas and Luhansk. The full-scale invasion changed everything. In the first six months, most of us lived in survival mode — constant blackouts, no electricity, no gas, no internet. People were in shock and didn’t know how to react to each new attack. Now, we’re in a different phase: we are trying to adapt and to keep life and work going despite the circumstances. For the media, this means focusing on supporting local and regional press freedom, because local journalists are the first to react when something happens — and they are also the first to counter disinformation and Russian propaganda, which is very active in spreading fake news. But it’s becoming harder. The recent attacks on energy infrastructure have caused severe power outages. Before I came to Madrid, I spoke with several local editors who told me they couldn’t even charge laptops or phones. Imagine trying to publish news under those conditions. Economically, it’s also devastating — the market has collapsed, subscribers have been displaced, there’s almost no advertising. Many male journalists have been mobilized into the armed forces, so most newsrooms are now run by women. They manage the teams, worry about their children in school during missile attacks, their husbands at the front, and their colleagues’ safety — all at once. It’s extremely hard, both physically and psychologically, to work under these conditions.

What does freedom mean to you now, after these years of war?

Freedom now for me feels very physical. It’s no longer an abstract value, it’s the air you can breathe when missiles and drones are not flying, it’s the ability to speak the truth without fear, to call things by their real names. Freedom for me means responsibility, courage, and an unbreakable bond with those who paid the highest price for it.

For it is very simple words about the people around: Ukraine’s fight is the story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things to defend their dignity.

How do Ukrainians view Europe today? Do they still feel supported, or has that support started to fade?

We still see and feel a lot of support — politically, institutionally, and personally. Millions of Ukrainian mothers and children became refugees, and they were welcomed with warmth and humanity by European citizens and governments. That solidarity has saved lives. The same is true in the media field: many European outlets continue to highlight our stories, continue to ask what is happening in Ukraine. Of course, attention shifts — there are elections in the United States, the war in Gaza, many global events — but awards and meetings like this are opportunities to bring attention back, to remind people that the war is not over. And I see that European journalists still want to listen, still want to tell our stories, because we are fighting for the same values they live by every day — only we have to die for them.

About journalism now, Do you believe journalism can still change something in a time of war?

Absolutely. Journalism cannot stop missiles and drones, but it can prevent silence. It can protect memory about the frontline cities and villages which are disappearing now under russians attacks, confront lies, and remind the world that every number has a human face behind it. In times of war, truthful journalism becomes an act of resistance — and sometimes, the only one left.

When you look at your work today, what are you most proud of?

I’m proud of the media community we have built – journalists who, despite fear and loss, continue to work, to investigate, to tell the truth, colleagues from a lot of other countries who are externally supportive as professionals and on very human basic! I’m proud that we, as an association, managed to unite independent regional media, helping them not only to survive but to find strength in solidarity. That unity is our quiet victory.

And personally, I just try to turn fear and exhaustion into active movements. I remind to myself why I am doing that: for my 4 kids whom I really want to live in a peaceful Ukraine, for my colleagues in regions, who are still reporting under missiles.

Finally, how can European media continue to help keep Ukraine visible and ensure its story is told?

This is a very important moment for journalism everywhere. It’s crucial not only to follow the news cycle but also to keep following the long story — to report not just the headlines but the ongoing human reality. The war in Ukraine is as brutal now as it was in February 2022. More people are dying, more are injured, and we must not be forgotten. Journalists must keep telling the stories of ordinary people, because behind every headline there is a human life, a loss, a story. Every day in Ukraine, at 9 a.m., we observe one minute of silence for those who have been killed or are missing. In that moment, everything stops — buses, cars, children in schools. It’s a collective reminder of the price we are paying. But for many Ukrainians, one minute is not enough. The list of what we have lost — homes, friends, children, husbands — is too long. We need the world to keep listening, to keep remembering.

Please, don’t let fatigue replace empathy. The war did not end just because it left the headlines. Every day, Ukrainians are still defending the very basic European values which was built upon: dignity, democracy, freedom. Freedom is not something you was born with. Sometime to have to prospect it, fright for it. And sometime – you need to die for it. As we are doing now, in Ukraine

Today, appart from violence, media faces challenges of all kinds, from financial to technological. What do you think are the main challenges facing the media today, and what do you think is the role of media associations in addressing these challenges?

The biggest challenge today is not only to survive – financially or technologically – but to remain trustworthy. In an era of propaganda, disinformation, and shrinking revenues, journalism must protect its credibility as its greatest asset.

Media associations play a crucial role here: we unite, defend, and empower. We create spaces for cooperation instead of competition, offer protection when individual media are too small to defend themselves, and help find sustainable models that allow truth to survive in a market driven by clicks.

Would you like to add any final thoughts?

The war forced all of us in the media to redefine ethics. For me, the hardest part has been deciding how to continue our mission of truth while ensuring the survival of our teams. It’s not a single decision, but a constant one – how to protect our people, our values, and our voice at the same time.

Aside, meetings like this give me a voice to speak on behalf of those who cannot — journalists who were kidnapped, tortured, or killed in Russian captivity; reporters and editors who remain imprisoned or trapped in occupied territories; and the more than 330 media outlets that have been forced to close because of the war. We still need attention, we still need support, and we still need solidarity to continue this fight for truth and freedom.